W H A T ' S T H E W O R D ?

Tell me brother, have you heard from Johannesburg? (in a Gil Scott Heron voice)

South Africa is mostly known for its Afrikaans Apartheid regime, the segregation, the violence and the poverty - despite being known as one of the richest gold mining countries in the world. 20 years after Nelson Mandela got elected in a democratic election, our perception of the country is more or less based around Cape Town’s models and photoshoots. But today the Apartheid that divides the communities and cities is far from being over. Inequality in income, education, and living space is still a major problem for the so-called “Rainbow Nation”. Our understanding of South Africa is also still shaped by the white minority. So it was important for me to invite a black artist to Berlin and hear their story and how they want to portray their communities. One of these great artists is Musa N. Nxumalo. So let us hear his story…

Hey Musa, great to catch up with you and happy you joined the “On Fire” photography group show here in Berlin. People are excited and want to know about this kid from Soweto. So… what’s the word?

I am good, man. How’zit?

Could you introduce yourself and give us a short overview of your life and how you got into photography?

I am Musa Nxumalo. from Soweto, South Africa. I came into this by chance, after school, like any other kid from the townships, I had limited choices on what to do with my life, or at least I imagined that, so I hated the idea of just getting a job and doing a regular 9-5, despite the fact that finding a job is a mission on its own. I had been a music enthusiast throughout my teen years and I couldn’t imagine myself doing anything outside of the arts. A friend of mine who knew about my interest in photography and all things art, referred me to a photography training institution in Johannesburg - I held a camera for the first time there and I just couldn’t let go of it.

Tell us a little more about the famous Market Photo Workshop (founded in 1989 by world-renowned photographer David Goldblatt) and your education there.

There were a couple of incredible photographers coming out of their education there over a span of decades. So you’re in a line of great storytellers and image makers… I would say. I went there and I immediately felt as though it was my home away from home, likeminded students and staff members, surrounded by all things photography-related, the darkroom Macintosh computers, cameras, printers, and the likes of Lolo Veleko, Santu Mofokeng, and Jodi Biber coming in and out once in a while. Exhibitions every two or three months, public talks about sociopolitical issues that we face as a country and continent...man I wouldn’t trade that for anything, the school brought out my passion for learning and political awareness.

Researcher, documenter, participant. How would you describe your role as photographer?

I have always seen myself as a participant and a documenter, but I now consider myself as a documenter and researcher, which for some reason sounds weird because I don’t see how can I separate myself from being a participant anyway...

Do you have people you look up to from the MPW or in South Africa in general?

Yes, John Fleetwood, the head of Market Photo Workshop, he became my boss for some time at this place and I have always looked at him in awe. He is a hybrid, manager and leader... man I can go on and on!

Who are your heroes that influence you and your work the most?

Right now, Kanye West, and there’s a guy by the name of Thapelo Mokwena, he is an actor and filmmaker from here, these are two guys that are influential to me right now.

You are part of the so-called “born-free” generation from South Africa. Born shortly before and after 1994, the year of the first democratic election, that ended the Apartheid regime. How is your generation dealing with the “free” rainbow nation?

We are 20 years old, as a “free” South Africa… rainbow nation is too ambitious at this point, it is an idea that we could still achieve should the white supremacy fall. At the moment, we are nowhere closer to being a Rainbow Nation, some colors are still desaturated for us to wear the rainbow nation hat.

And what does this label “born-free” mean to you?

It’s a lie, maybe this applies to the white kids of this generation who get double benefits by coming from colonial power and who still live “freely” under the new democratic South Africa. For black kids, it is a completely different story my man! I hate this born free tag because it is not true.

Another term used often is the “lost generation”. How do you feel about it?

They’re right, how can I not be lost when my leadership is not showing me the way but is busy drifting sideways? I actually find that really funny coming from a generation before us, it’s like they are confirming their failure as leaders and elders but me I don’t believe we are lost, I believe we are designing ourselves and that my friend is not an overnight job, it is a process and we will continue encountering brick walls, and we will overcome and continue our journey. Think In Search Of... bro.

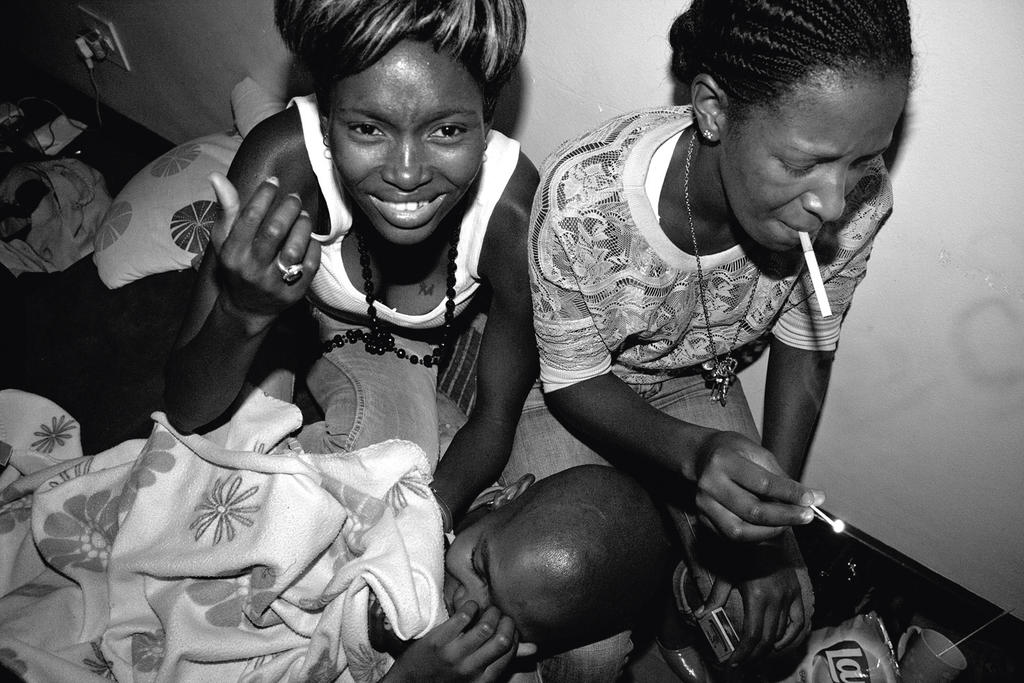

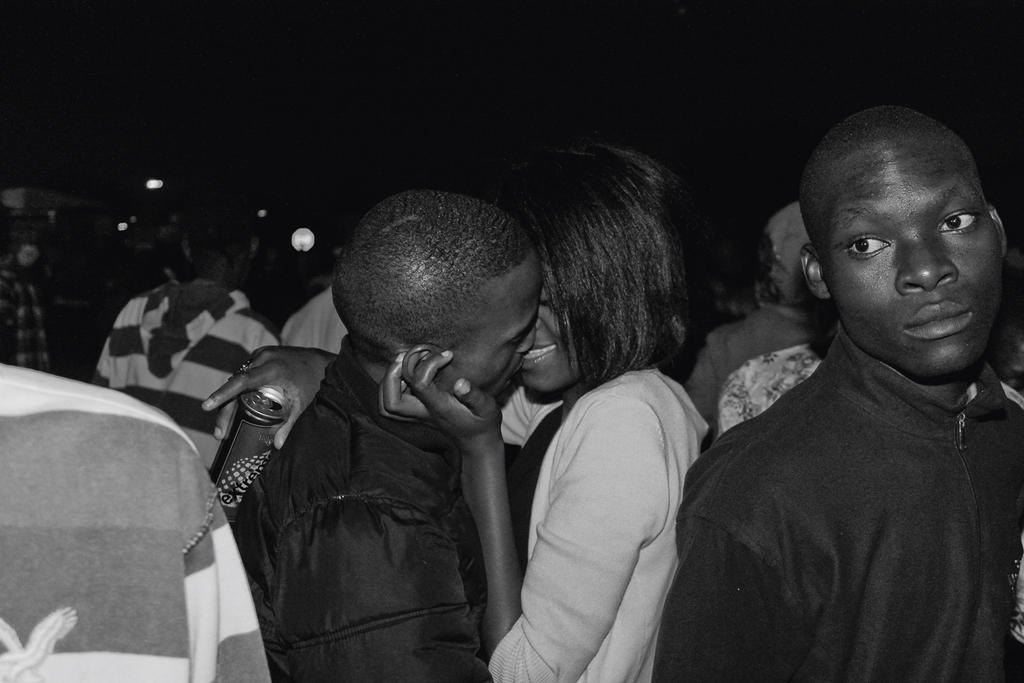

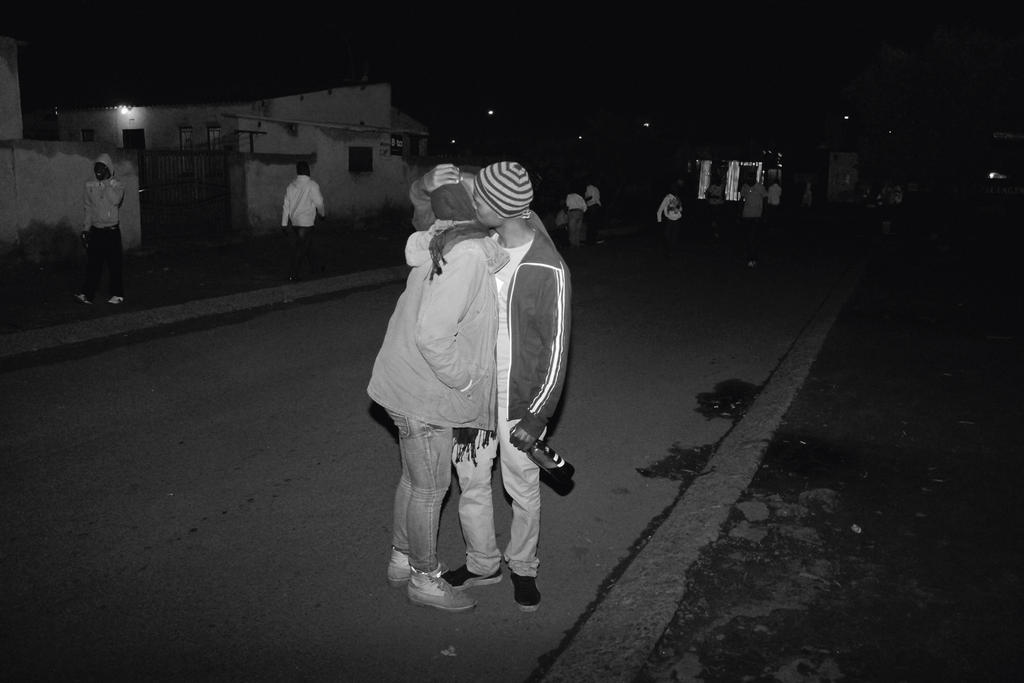

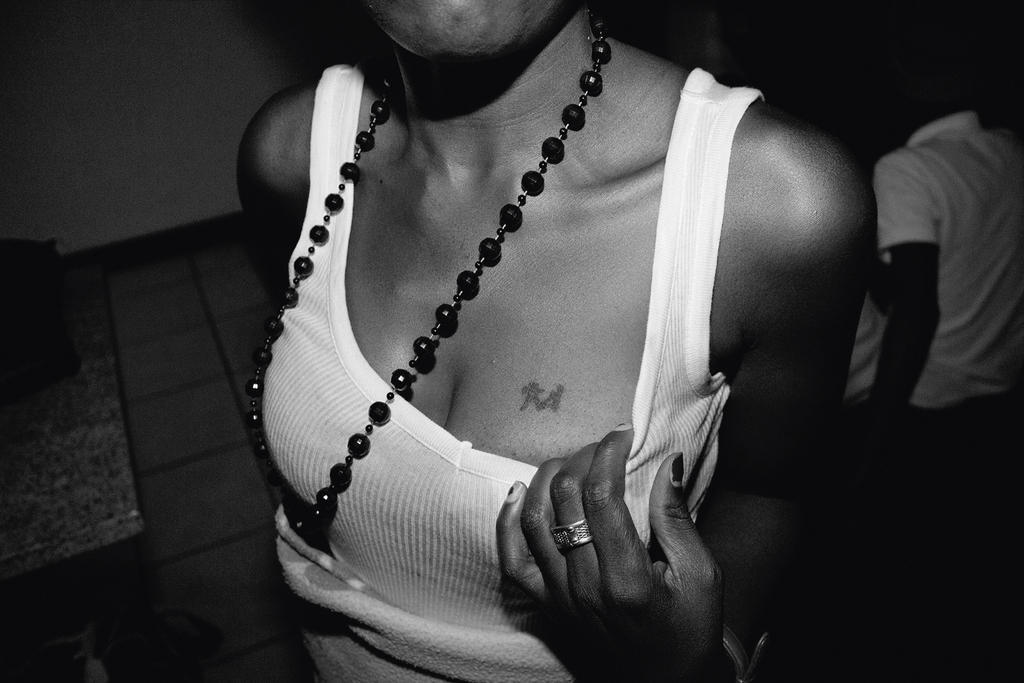

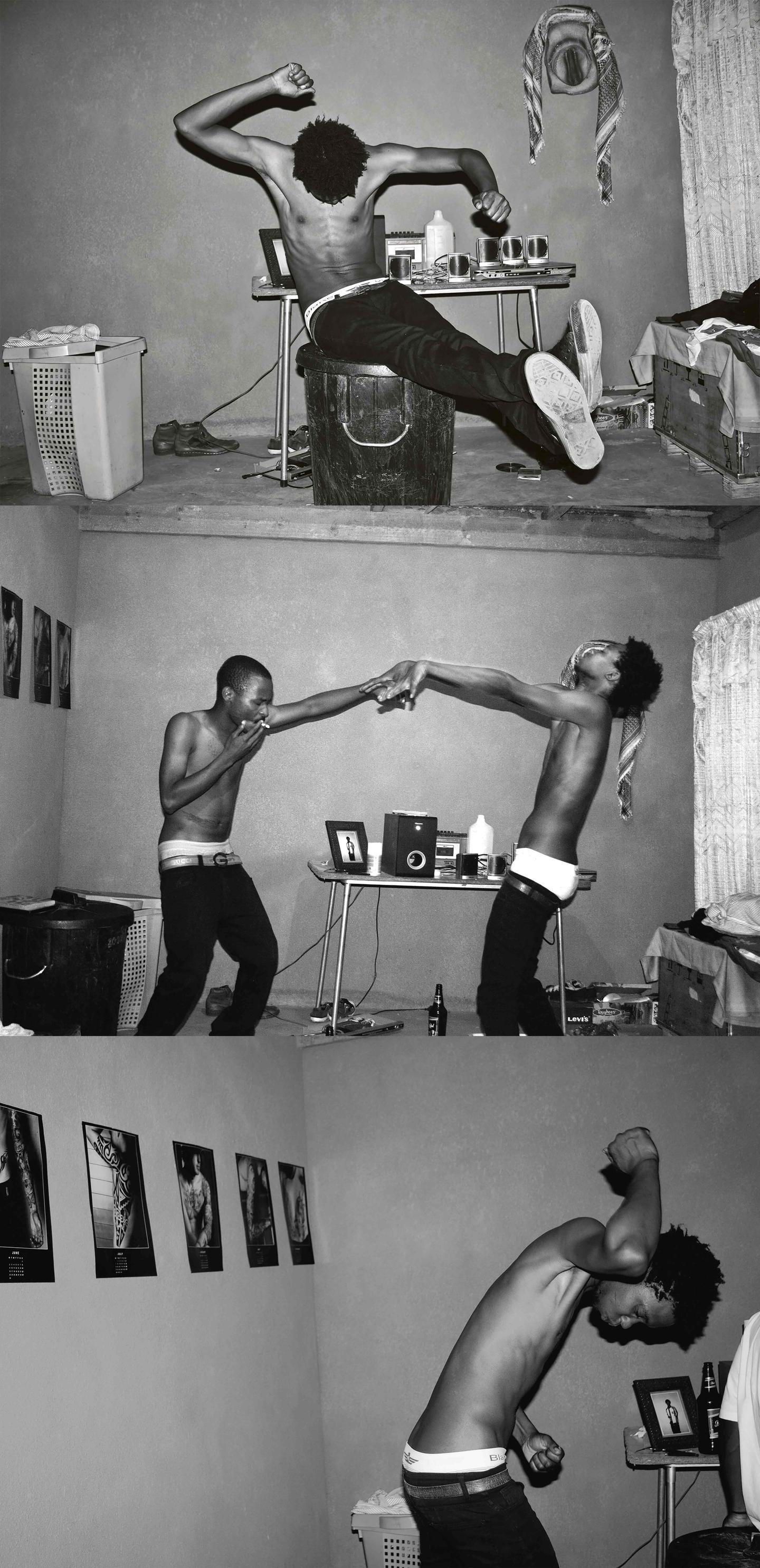

„In search of…“ is the title of the body of work that includes most of your photo series? “Alternative Kidz” and “Friends/Damned” where you document you and your friends’ life? As well as the family album, titled “A Half Built House” and “In/Glorious” that document your life surroundings of family and the reality of the township? What are you searching for? In your life as well in your work?

Like I said before, we are a young democracy, only 20 years, this means we still have a lot to do in order to develop our character as a nation, especially as young South Africans. This project came from the idea that, I wanted to look at where I am or where we are as young black youth from the townships, look into our personal history a little bit as the means of developing a thick skin for what we want and hope to achieve in the future. Without doing this, I believe we will fall for these ideas that are thrown at us like “Born Frees” and “Lost Generation” nonsense. So, In Search Of... is a model for me to find a way of shaping myself from the complications of our current position and historical imbalances.

The body of work that you show deals mainly with your surroundings, family, and friends. Could you tell us a little more about it?

It’s a small part of Soweto called Emdeni, and this is where very little if anything happens here in terms of the arts, it is a bit discouraging you know, the fact that this is one of the places where you see a great amount of young people who are not active economically due to unemployment and lack of access to quality education. This is how the idea of documenting it came about, for some reason, I felt like Alternative-Kidz gave the notion that we are alright, but the reality is we are not. And this work for me is somehow the beginning of me showing concern with these issues and opening a platform for my artworks to speak to these issues.

I recognized, that a big subject within South African photography is “space”. But in a political sense. Who owns the space or soil? Who is allowed in this space or landscape? These questions clearly arise from the South African history of racial segregation. How alive is this subject today for your generation? And how aware are you of this subject in your daily life and work practice?

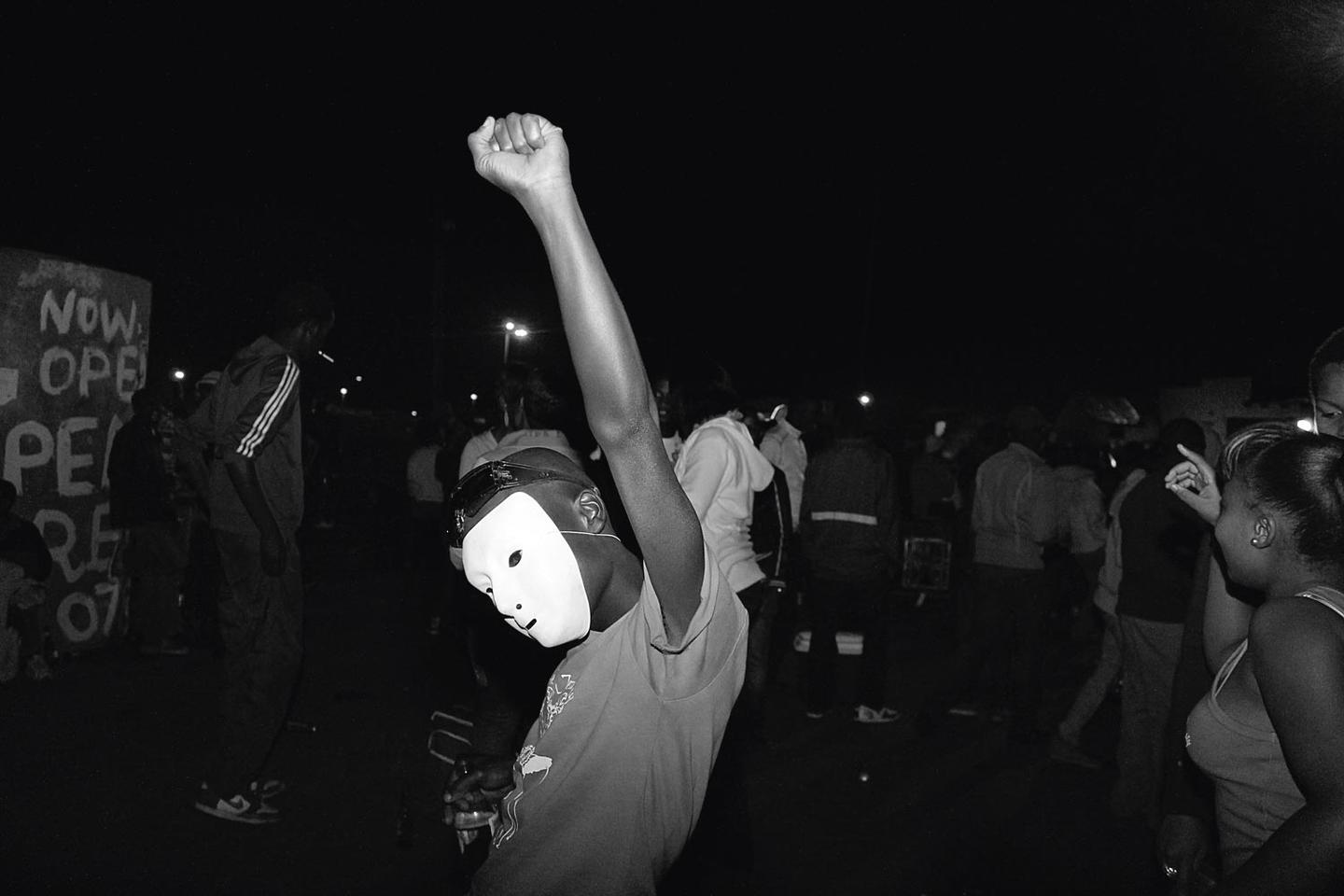

We are very much aware of these issues, and in fact I feel like we are a ticking bomb. Especially since the emergence of the newly formed opposition EFF (Economic Freedom Fighters).

What is the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) and how has it affected your generation?

It is the BEE Act No. 53 of 2003 that sought to fix the economic imbalances of the past, however it was criticized a lot, you know, arguments like, what is black? How do you scale it within the South African context etc. In 2004 it was changed to Broad-Based Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) - for me again, a brilliant idea, but when it comes to implementation it is not so great, again when you are in the townships, people just hear about these ideas and it is extremely difficult for them to access them.

With your series „Alternative Kidz“ you portray a part of your generation that doesn’t fit in the cliché that the world might have from South Africa. Is it important for you to play with these expectations?

Of course, hence the title and the context of the work. But you should not forget that the work dates back to 2008, when the idea was still fresh in a sense that other than Lolo Veleko and the smarties, you saw almost nothing of such alternative-cultures. Today we are just a splash of various street cultures that are common globally in such a way that I personally crave that old school or post 1994 Kwaito style and stuff.

In your imagery of the townships you never come close to the so-called “poverty porn”, a term and concept I first got introduced to, through our mutual friend Ayana Jackson. It’s part of the image the Western World has on Africa and seems so obsessed about. How do you approach this issue?

The idea is that, I don’t want to make images of what I don’t want to see. It’s easy to perpetrate a stereotype whilst you are intending to fight it. Therefore for me, if I fight it, I don’t recreate it.

For me, Johannesburg was an eye-opener, on a lot of levels. The energy of this city just grabs you and pulls you along. But also the big social gap between communities and neighbourhoods. Can you give us your personal view on your city?

3.4 million youth between the ages of 15-24 are currently not at school or working, and we have about 98 million adults that have never went to school in South Africa. This is mostly the black population of course, the current #FeesMustFall demand speaks to this issue and it’s really sad that, as black people in South Africa, we are still deprived of our rights like education and access to economic freedom, this is a result of the Apartheid system that still continues to benefit the white minority until this day. We are simply caught up in a web of social injustice that streams from Apartheid and that is seriously frustrating.

There seems to be a burst of super talented artists and cultural makers all over the city. Please describe the art scene in Jo’burg and its connection within Africa and the rest of the world?

I am very ignorant when it comes to art scenes and culture in Johannesburg, I am not in the position to speak about that, I have become more and more introverted, I stay in and read books a lot. I guess it’s another way of looking for inspiration in a way that I have not before. I was more outgoing and more clued-in to art scenes and cultures in Johannesburg before, but I am now more of an inverse to that.

You travel quite a bit. Is it part of your search?

I travel because of work, I haven’t traveled in a way that I really want to, as in to just pack my bags and be on the road for months, I still want to do that.

Thanks a lot man & hope to see more of your great work in the near future.