Beneath the Surface

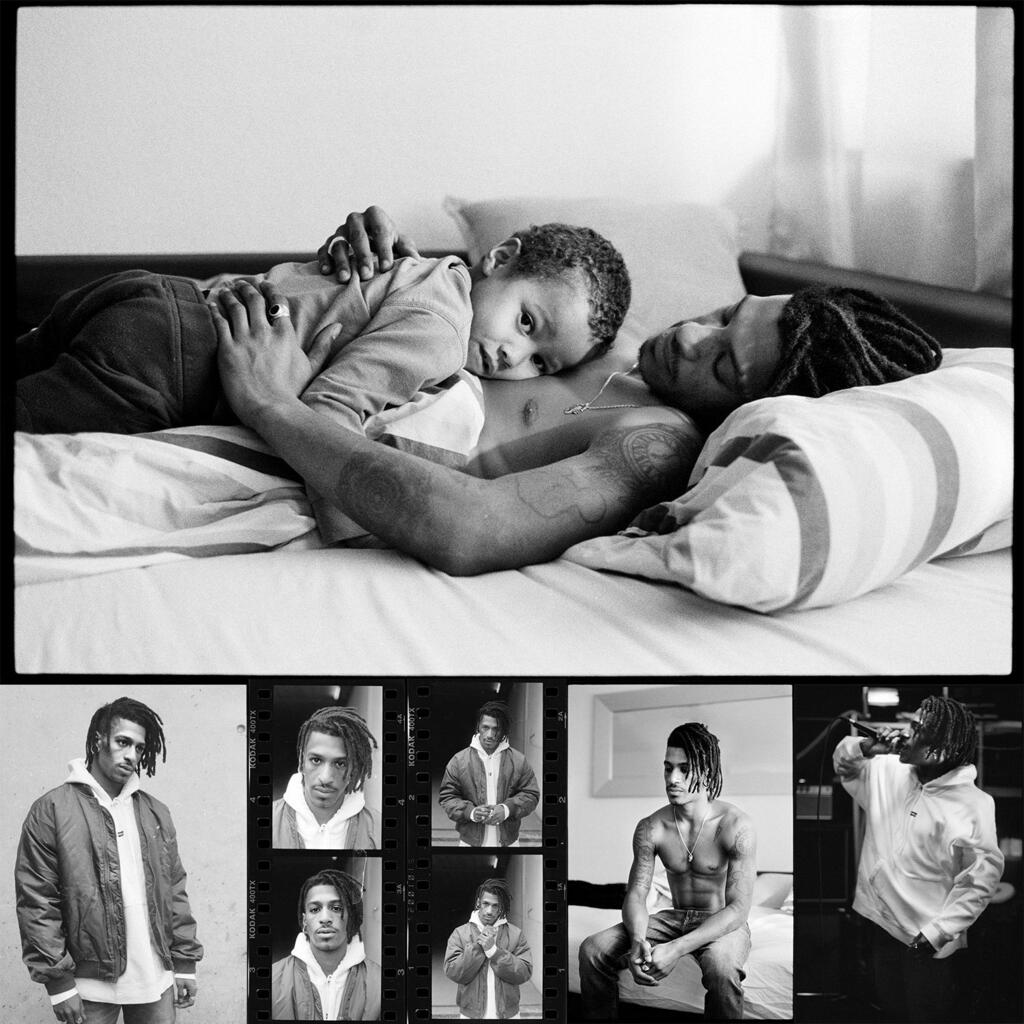

Owen Harvey - The Photographer Documenting A New Era Of Masculinity

Here & Now: In Partnership with Levi's Performance Denim

Text by Hazel Sheffield

Photography by Imogen Forte

Whether on the street or in the locker rooms, Owen Harvey has focused his camera on men for whom appearances mean much more than just fashion. Without realising it, he’s developed a body of work that reflects the changing face of masculinity – redefining himself along the way.

It’s Saturday night and Owen Harvey is squeezed into the corner of a bar in an East London vintage shop. The place is cramped and sweaty, the smell of beer and cologne in the air. With his jacket bunched up, his backpack crushed against a wall, the photographer holds a fifty-quid camera in his hands, ready to shoot. In front of him, a dance floor teems with characters from another era: skinny men in high-waisted suit trousers, burlesque dancers in tasselled knickers, girls in short dresses with heavily painted eyes.

Owen is shooting film, so there’s no way to know if he’s getting anything. But he instinctively knows how close he should be. He has spent hours practising where to stand in order to get sharp pictures, has spent years photographing characters who know exactly how they want to be seen.

“Photography, for me, is not just about saying something,” he says. “It’s about exploring: having an exchange with people, trying out different roles, finding yourself in challenging situations.” - Owen Harvey

At 29, Owen’s career has taken him from ’60s nights in London clubs to the streets of the Bronx. He’s slept on hotel floors in Blackpool and in shared apartments with models in New York. Every night starts the same: the unsociable hours, the cheap camera so that he can walk into unpredictable situations without worrying about his kit, the waiting in the shadows watching other people’s lives unfold.

He has already picked out the faces he’d most like to photograph tonight: a beautiful long-haired boy on the stairs with porcelain skin, a man with a handlebar moustache in the corner, a woman in a blue dress pawing at someone else’s thigh. From across the room, a young guy in a navy suit – buttoned over a bare chest – comes over to say hello: Owen has recently photographed him for a series about dandies in Soho. They greet each other warmly.

This is how it usually ends – with friendship and the invitation to take more pictures – but rarely how it starts. Some of his best subjects told him to fuck off when he first appeared with his camera. It comes with the territory when you’ve made a career taking pictures of skinheads, mods and lowriders: the kind of subcultures that thrive on a sense of bravado and belonging. “Everyone needs a group to feel part of,” he says. “Otherwise the world is a lonely place.”

Owen is happy not to belong. In person, he's amicable and down to earth, the kind of person who prefers to stay seamlessly low-key rather than stand out in a crowd. “I'm a loner at heart,” he says with a nod, sounding nonchalant but self-assured.

The photographer spent his formative Saturdays watching Wealdstone Football Club, a non-league team that gained support from a generation priced out of Premier League games in the ’80s and ’90s. Owen never loved the football, but he was fascinated by the stories of fighting on the terraces at Chelsea. His father, a fireman, came from a working-class family in North London, but married into the middle-class. (Owen’s mother, a private school teacher, came from a more affluent background.)

Owen grew up curious about the two sides. When he was 12, his parents broke up, his dad moved out and his older brother moved abroad, leaving him to figure out what kind of man he was going to be on his own. While Owen absorbed a lot from those conversations about violent football clashes, told by men who came home to be caring husbands and fathers, he grew to question the ways they shaped his understanding of how men behave.

At 14, Owen joined a band. Saturdays down at Wealdstone FC were replaced by trips around the UK for shows, his dad behind the wheel of the tour van. Owen’s first connection to music came from poring over the sleeves of his dad’s records. He can still remember every detail of the inside cover of Quadrophenia. “My dad was a huge part of the band,” says Owen. “A lot of that was because he didn’t have those opportunities himself when he was young. But he was also playing ‘weekend dad’. It was a connection and [a case of] wanting to be supportive.”

When Owen was 23, the band broke up. “My whole identity was the band: music was the way I expressed myself and the way I managed to get things off my chest.” But he had also invested 10 years in it at the expense of his relationships, his education and his health.

At one point in his late teens, he would stay up until his mum got ready for work at 6am, then sleep until 7pm every day. “I was hugely depressed and quite difficult as a character because I was not looking after myself as a human,” he says. “I was interested in exploring these two sides [his parents’ different backgrounds] to get a better idea of who I wanted to be.”

Owen had often been around photographers through his work in the band. But after taking it up himself, watching others through a lens offered a means of self-discovery. He went back to education, doing a course in photography, and started taking pictures of people in his hometown of Watford.

But over time, Owen found himself gravitating to projects on hyper-masculine subcultures without even realising. “It took another photographer to point that out. He told me, ‘You work is 100 per cent about machismo.’ And that caught me off-guard. I had to start questioning it and figuring out why.”

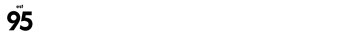

Owen’s best shots capture a vulnerability at odds with someone’s appearance. Like Sosa, an intense New Yorker who showed him around Harlem. In one picture, his biceps bulge out of a sleeveless hoodie as he leans back on his customised car. He looks tough, but his brow is slightly furrowed and there is a softness in his eyes. Or Mykie, a skinhead Owen shot in Hackney. In a photo that appeared in the National Portrait Gallery, she is 16-years-old, baby-faced and sat stiffly on a wall, her mini-skirt risen up to reveal bruises on her thighs. There’s the duality: the innocence and aggression. “Everyone is looking for a sense of belonging,” he says. “People act for two reasons: out of fear or out of love, and we all have that in common.”

“Photography is not just about saying something, it’s about exploring... The people I photograph are a mirror of myself.” - Owen Harvey

“But I do think the idea of masculinity is changing,” he adds. “I don’t think there are as many ‘rules’ anymore; things are less rigid. I see that a lot in the people I photograph. There may be a tough exterior, but inside there’s quite a nice vulnerability and a softness to them. For me, finding comfort in that vulnerability is a strength. And I think that is naturally changing in a lot of people’s outlook.”

It’s approaching midnight on Saturday night. Owen could be at home watching TV or in the pub with his friends. But he’s in a vintage shop turned into a club, camera raised, always looking for the same thing: a little piece of himself reflected back in the eyes of a stranger. “The work has been about getting an understanding of people by giving myself an excuse to have a conversation,” he says. “And the more I learn about people, the more I feel content with myself.”

Here & Now is an editorial partnership between Lodown, Huck and Levi’s Performance Denim, which is available now.