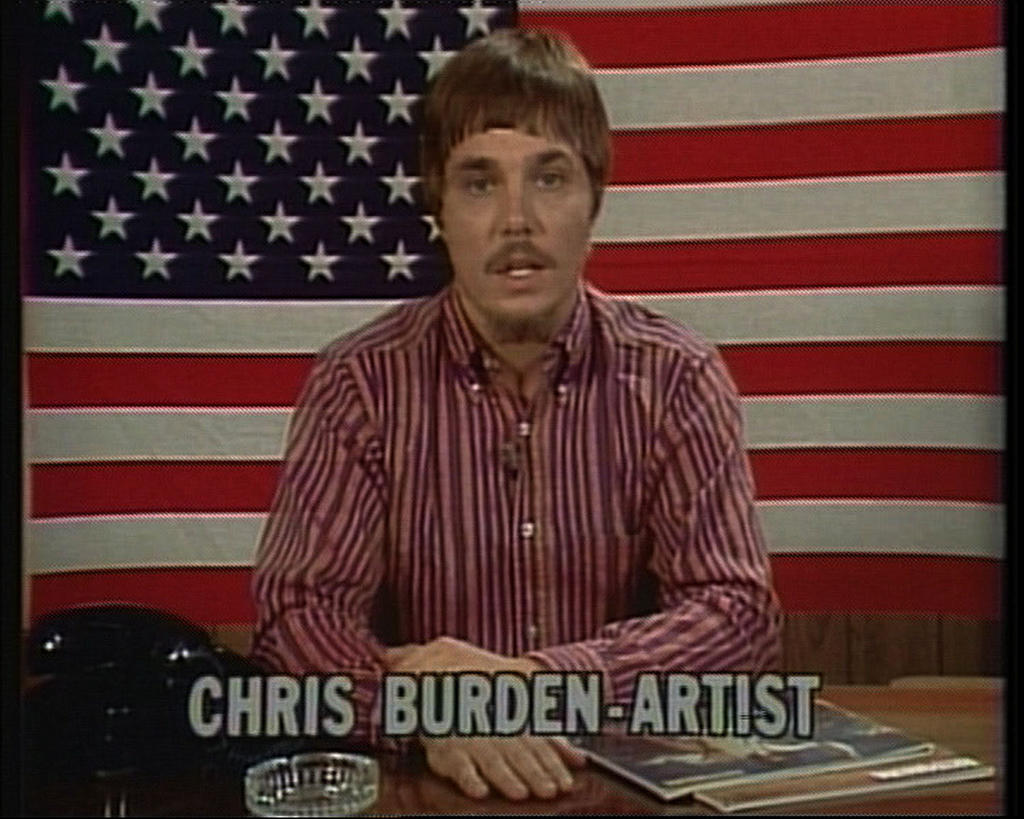

r.i.p. chris burden

through life never soflty

Chris Burden (April 11, 1946 - May 10, 2015). The original interview was published in Lodown #66.

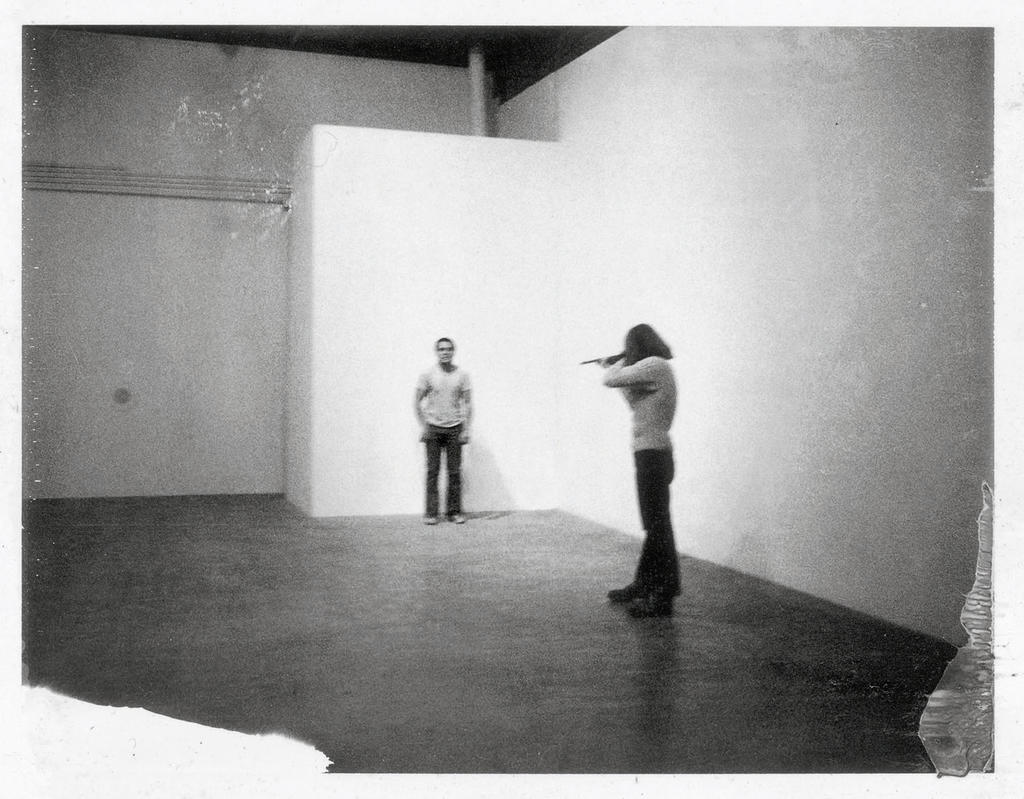

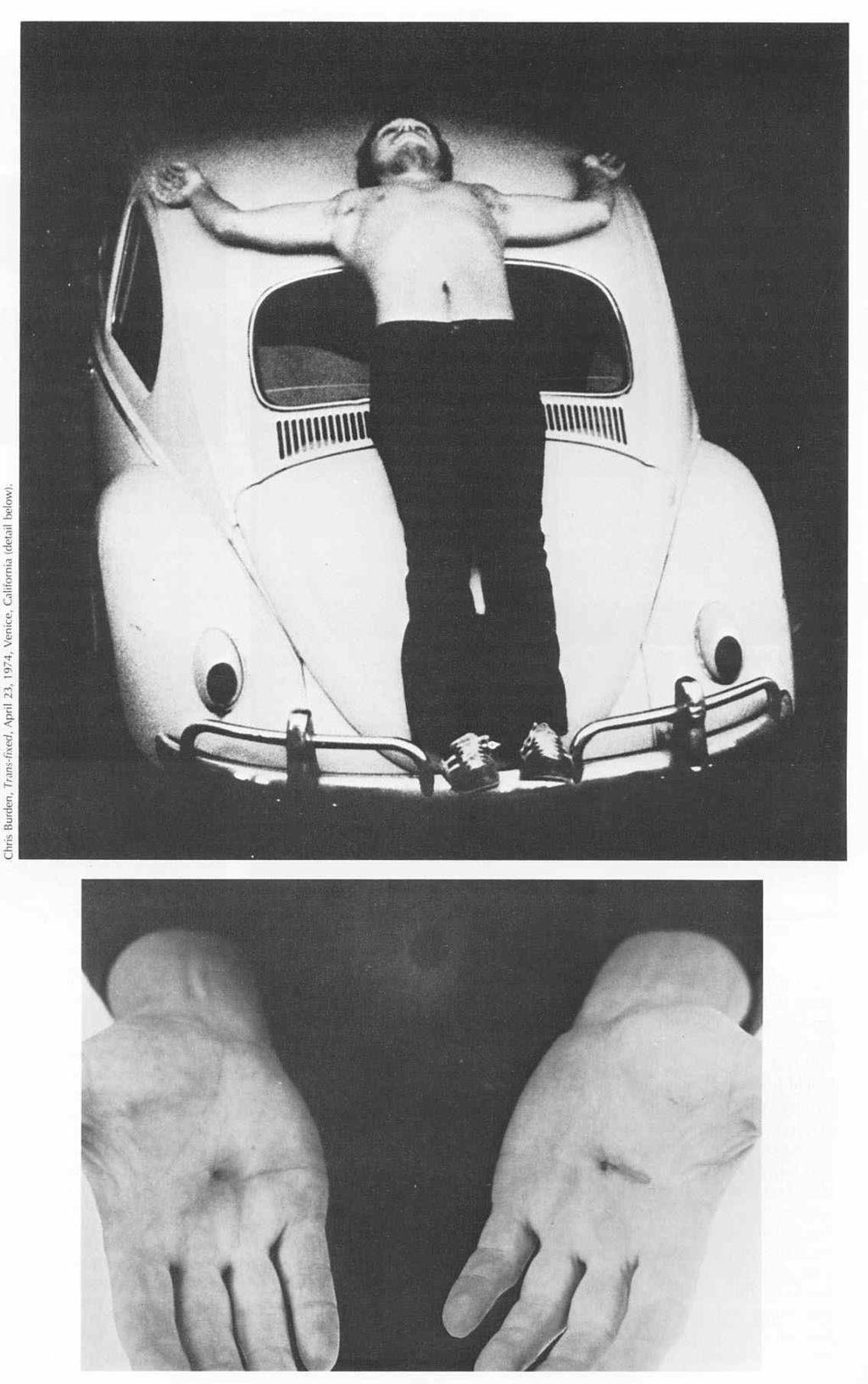

Not many people can claim to have had a friend shoot them at close range with a .22 rifle (“Shoot,” 1971). Even fewer can say that they spent five whole days in a locker (“Five Day Locker Piece,” 1971). Fewer still, the number of those who seriously tried to breathe water until they collapsed (“Velvet Water,” 1974), fired a pistol at a Boeing 747 flying overhead (“747,” 1973), got nailed crucifixion-style to a roaring Volkswagen Bug (“Trans-Fixed,” 1974), spent 22 days lying on a triangular platform in some remote corner of a gallery (“White Light/White Heat,” 1974), crawled through 50 feet of broken glass without using their hands (“Through The Night Softly,” 1973), or almost electrocuted themselves on the Venice boardwalk (“Doorway To Heaven,” 1973). Whereas his seminal and controversial performance/body art endurance pieces helped Chris Burden (b. 1946) establish a reputation as a serious bad-ass, someone more than willing to see things through to the end, the Topanga-based artist has been pushing boundaries for almost four decades, shifting from conceptual body-related works to various other fields and artistic approaches: for “Ghost Ship,” (2005) for example, he constructed a self-navigating yacht (using GPS and a system of hydraulic cylinders to trim the sails), thus merging art, traditional craftsmanship, science, technology and history, while “The Other Vietnam Memorial” (1992) was one of his most obviously political pieces. Other landmark installations and sculptures include “What My Dad Gave Me,” a 65-foot skyscraper built entirely of toy construction parts, “Urban Light,” a monumental collection of restored and fully operational vintage lampposts from the city of Los Angeles, and his indefinitely postponed “One Ton One Kilo,” a piece which just recently made the news as the owners of the Gagosian Gallery, who had bought one hundred one-kilo bars of pure gold from Stanford Coins & Bullion, had to find out that the gold intended for the piece was frozen, i.e. it couldn’t be delivered because Stanford was charged with an alleged eight-billion-dollar fraud. Since “Beam Drop,” (1985; 2008) a provocative statement against corporate architecture, is going to be presented for the third time this summer in the Middelheimmuseum in Antwerp, we reached out to Burden to talk about the importance of thinking “what if,” tuna fish can worship, and people who talk too much on the phone.

Chris, you grew up in France and Italy, how come? What did your parents do there?

My father worked for a non-profit organisation called Rockefeller Foundation, so he was stationed in Paris; and my parents didn’t divorce, but they separated and my mother travelled with us in Europe, so we spent time in Switzerland and Italy.

How does it feel to think back to those days? Is it a good feeling?

Yeah, I like Europe. It’s a little bit like going to grandmother’s house. I don’t know if I really would want to live there or not, but…

… but then you had an accident.

Yes, I had an accident in Italy. It was on a Vespa truck, a three-wheel truck, I was a passenger in the front, it turned over on a corner, and it crushed my foot.

Is it true that you stayed in hospital for an entire year afterwards?

Well, I didn’t stay in a hospital, but I didn’t walk for about a year, yeah.

How did that affect your life?

You know, I was a young teenager, and I spent a lot of time by myself, so I started taking a lot of photographs.

Did you dream of becoming a professional photographer at the time?

No, I don’t think so. You know, I was young; I was thirteen. I guess I just liked making things; I liked making images, so I think it was a creative process.

I see. When you moved back to the States, why did you eventually move to the West Coast?

Well, I have to say my parents got back together, and I went to a high school near Boston. In my last year in high school I went to California on a science foundation grant. I spent the summer in La Jolla, California, actually… taking pictures. And then I had an interview at Pomona College, which was near Los Angeles on Route 66, so that’s where I ended up going to college.

Did you learn anything at college that helped you later on with your work?

Yeah, I mean, I studied art and art history, it was a liberal art’s college. Then I worked in an architectural office one summer because I was a pre-Architectural major, and I didn’t like what I saw. And it was while I was working in that office that I decided that I wanted to become a professional artist.

Was it one definite moment when you made that decision?

No, I think it was an accumulation of things: being in an architectural office, I was the lowest person of the staff, so my job was to organise magazine stuff. And I had experience of working in the sculpture studios at Pomona College, where I could get immediate results. So it wasn’t really a specific moment, but at that time I just decided that I didn’t want to become an architect.

Let’s talk about the early live body art endurance/performance works: can you remember the feeling that triggered these pieces?

I think I was trying to discover what sculpture was, and trying to come to terms with it. I was trained as a minimalist sculptor; my teachers were into minimalism, and I was trying to distil or take away what’s not essential – and I came up with the conclusion that human activity in viewing a sculpture defines sculpture as a different form. You had to walk around it. The essence of sculpture was that it forces the human body to be active, to physically move. And from that I developed a series of works that were a little bit like exercise tools: they were designed to be used in a certain way; you either had to jump a certain pole, or hang from a certain thing. And if you did it correctly, you knew you were in the groove, but it you did it incorrectly, you were immediately aware of that because it was awkward. Later, the most important decision I made, I think, in terms of being in graduate school, was for my Master of Fine Arts show: I wanted to make a box and get into it, to be in an enclosure as my artwork. It was me being in a box that was the art. And I kept going back to the student art gallery, and I knew there was a series of metal lockers, like book lockers, and I realized that I should not make a box but I should use a pre-existing box. Therefore the artwork was entirely defined by my activity, not by the object. That was the beginning of the idea that I didn’t have to make an object to make art, that my activity could be the artwork.

Control is a central element to most of your work – danger control, situation control, even remote controlling a ship –, were there ever moments when you were scared, when things seemed to get out of hand?

That’s an interesting question. I think you need to think of them a little bit like science experiments. You don’t know the outcome necessarily but you’re very precise when it comes to the input. And then the output is something that you sort of accept as a given, you don’t always know what it’s going to be. I mean, you make a fantasy outcome and you believe in it so strongly that it enables you to make the work. You basically trick yourself because you make a fantasy outcome and that enables you to proceed.

Do you think the significance of any given piece always comes across to the viewers? Do you think it is the same experience for you and for them?

You know, there were very few viewers because my audiences were very, very small.

But still there were some people around…

I think I chose those viewers because they were either friends or artists that I felt some sort of connection to, so they would see things pretty much my way. Now, when we’re talking about looking at a picture 20 years later, you’re no longer a viewer of that action. You’re not a viewer, you’re just looking at some documentation and you imagine what it was like. That audience is different to the primary audience.

Seems like you didn’t even take that many pictures, though.

Well, I did take a lot of pictures, but the pictures that I chose to publish and release were carefully selected. Often it’s just one single picture of a performance because they’re symbolic images; they’re not supposed to give you all the information of what it was like to be there. They were simply touchstones.

One of them – I’m thinking of “Trans-Fixed” –, had some religious overtones, and actually other parts of your work had that as well… there was voluntary seclusion, ordeals etc. Is there a particular belief you subscribe to?

I mean I grew up in Europe. But you know I’m not religious: I believe in science, not religion. I guess you could call me agnostic; I’m kind of anti-religious, though I understand it gives a lot of people comfort. I have problems with people who try to preach, who try to convert people – that is very disturbing to me. If you want to worship a tuna fish can in your backyard, you should be able to do so, but please, in the privacy of your own home.

You once did a piece called “Honest Labor” – was that the only time that making art felt like “honest labor” to you?

Well, you have to see that these things were often responses to more specific situations. In the case of “Honest Labor” I was asked to go to the University of Vancouver, and I was told I could do anything I wanted. I didn’t want to talk to students or give workshops or anything, so I deliberately chose to distance myself from the actual physical university and to dig a trench every day. I invited people to come; and people, students, they could just come and help me if they so chose, but I would be there every day from eight to five, digging a trench. So, in lieu of going to the university and talking about my artwork, this was a way to respond to that specific situation.

Did people show up?

People came, yeah, they would dig a little, and then they’d get tired and bored. I didn’t get tired because I had a mission: to dig, every day, from eight to five o’clock. That was my mission. So that’s what I did.

Since you just said you didn’t feel like talking to students, how come you eventually became a teacher at UCLA for 26 years?

I mean, this was a special invitation to go to Vancouver; it was a one-time deal. I was a visiting artist. Teaching at UCLA was simply a way to maintain the livelihood, so that I could keep going to Vancouver, digging ditches.

Ha, I see. Did you enjoy it all those years?

At the end I didn’t enjoy it. Initially, it was okay. It was interesting, but as you get older the students get younger and younger, and after a while you feel like you’re taking care of other people’s children. So I have to say, at the end I didn’t enjoy teaching.

Has it influenced your work in any way?

It did in the sense that, because I was getting an income from teaching, I didn’t have to think about art sales. So it did influence my art, because it enabled me to do works that were not necessarily commercially viable.

Though some of your works must have been amazingly expensive to make – I mean, buying all the lampposts for “Urban Light” alone…

Yes, it was. It took eight years to assemble them all, and I took out a loan and sold some other artworks; but spending money on your art and your art materials is probably the best way to spend money. I don’t put money in the stock market, or hedge funds that just seems stupid. Especially these days, huh? Why would I give my money to some other person to invest? I should always invest in myself, in my art.

You also did those “TV Ads” – another good way to spend money. How have your feelings about television changed since?

They have changed, obviously. I think I did four or five different commercials, and when I say commercials I mean I was able to buy my own time on television by calling it a commercial. When I first started doing them, there was no cable TV, there was no satellite TV, it was simply five or six stations – ABC, NBC etc. –, so the question was how do you get on television. The answer is: you pay for it. They were a way for me to do an artwork that millions of people saw whether they liked it or not, or whether they wanted to see it or not, let’s put it that way. Back then it was monolithic, so it was as if god was sending down a message from above, and you never thought you could have a voice. But by buying time on television I was able to sneak around them and do something that they didn’t think was possible.

When exactly did you get more interested in technology, rather than physical danger?

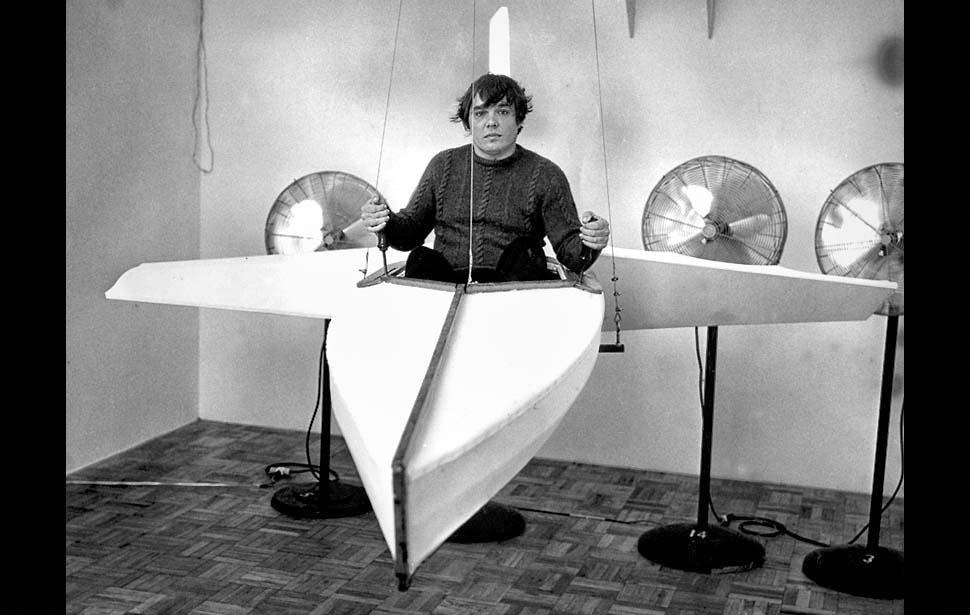

I think when I made that automobile, the “B-Car,” which was, I think, in 1975-1976, that was a turning point. I made objects in school, and the fact that I stopped making objects was also a financial thing, a way to survive. Because if you are a sculptor and you make objects, and you don’t sell them immediately, you’re going to have a storage problem. Painters have this problem to some extent, too. Doing the action works and the performances was a way for me, when I came out of school, to continue making art without any tools. I mean, a camera and a file cabinet, but that’s really all I needed. So it was just a practical way to keep making art. When I made the “B-Car,” that was sort of a turning back, I wanted to make objects again, and I did do some performances after making the “B-Car,” but that, I think, was the beginning of not doing performances.

And ever since then you’ve needed a lot of storage room.

Yeah, I have a large property and a big studio, and, I don’t know, 15, 20 employees, and a corporation. You know, I’m here in Topanga most of the time. I don’t particularly like to travel, but I have to for my business, so I do it when I have to. But most of the time I’m here, and I have several projects going on and I oversee them all. Have you heard about this recent problem I had with this gold?

Yeah, the gold that was bought for “One Ton One Kilo” which they couldn’t deliver.

Yeah, it’s really complicated. But it’s interesting to me, this simple idea of exchanging money for gold, which should be a very clean, simple transaction, but not in this case. What can be so complicated about it? It’s something people have been doing for thousands of years.

It certainly is crazy. But let’s talk about another recent piece: what can you tell me about “What My Dad Gave Me,” the skyscraper? How did that one come about?

You know, those parts are from American Meccano…

… Erector sets.

Yeah, it’s a different way of assembly. The parts are different, they have a little curl, so they go together differently and it’s a much cruder system. It was invented in about 1909, and the inventor, A.C. Gilbert, he was leaving Manhattan, and he saw all the big buildings going up, so he wanted to make a metal construction toy that children could use to build buildings, cranes, bridges, etc. He was so excited, you know what I’m saying, about what he saw was going on. So I collected the old parts, but they’re very hard to find and get more and more expensive, so maybe six or seven years ago I started reproducing these parts out of stainless steel.

Wow, you made them yourself.

Yeah. We copied the old parts, but stainless steel is much better because it doesn’t rust; the old parts would rust very easily. So I did a whole series of bridges with them but I always wanted to build a building using these parts. And when I was offered the Rockefeller Plaza, I immediately knew that I had to build a skyscraper. It was my engineering, but it had to be confirmed by a licensed engineer. So we built a sculpture that’s the size of a building, though it’s the model of a bigger building. It’s five-storey high, so it’s as high as a five-storeys building, and it’s a poetic interpretation of a skyscraper. It’s not an attempt to be a copy of the Rockefeller Building. We put it up in one night; the height was limited by the length of what I could ship across the United States on a truck, because the city of New York will only let you close Fifth Avenue for six hours.

How do you think your more recent pieces like “What My Dad Gave Me,” “Urban Light,” or the “Ghost Ship” are linked? I mean, some of them have model character, some of them have an air of nostalgia, e.g. in the lampposts, the old Erector parts…

Well, the “Ghost Ship” is quite nostalgic, too.

Right.

I think it’s about taking parts of history, for example: the skyscraper, “What My Dad Gave Me,” is a reference to my father being an engineer, and if I told somebody this idea of building a 65 foot tower with these flimsy pieces of metal, if I took that idea to an engineer and showed him the material, he’d say, “You’re crazy. Can’t be done. This is much too weak. This has to be engineered. Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.” But in fact, you can make something with it; I think it’s about having some sort of a vision and the determination to trust in your instincts. With the lamps, these beautiful artefacts from the city of Los Angeles, it was my duty to preserve them, a little bit like a preservationist, because the history of the city is so quickly erased. So, it was a long process: I put the lamps around my studio, and when the museum in Los Angeles wanted to purchase them, I had another 55 or 60 that I hadn’t restored, and I said “You have to buy them all,” and now they have become a building; a building with a roof of light, as opposed to copper or asphalt or concrete. It feels like you’re in a very traditional Roman piece of architecture because of the columns, and it becomes kind of iconic for the city, which is nice. It’s a place on Wilshire Boulevard; and apparently people gather there every evening at sunset and wait for the lights to go on – it’s become a big part of the city.

Yeah, though since you just said that people would react by saying “You’re crazy,” it reminded me of your earlier performance works where everyone also said, “That’s crazy. What kind of person would do that?! He has got to be crazy,” don’t you agree?

Yes, but craziness is an abused term. It just means I have an active imagination; that I’m willing to do what it takes to see it through, to get the results.

Some of your work has been political, like “The Other Vietnam Memorial,” are you still interested in political statements?

Well, what is politics? You know, I’m interested in exposing the other side of the coin, because often people only think in one way. Sometimes if you reverse it and you go “what if…,” “what if we did it this way instead, the opposite way”. If you take something and you’re trying to reverse it, to me that’s interesting. The “Vietnam Memorial” came from looking at the miniature version of the Maya Lin War Memorial, that’s in Washington, it went around the country and would go to the little towns – people could come and leave their flowers and letters, but literally it only had one side. And I kept going around the back of the plywood, thinking: “Well, shouldn’t the Vietnamese names be on the backside?” But that’s what war memorials do: they only celebrate one side. So I had the idea that I should make a memorial that dealt with the fact that there were over three million Vietnamese killed… and actually, when I did this sculpture, it was about the time of the first Iraq war, the one with George Bush Sr. But I think the new piece with the gold is in some ways political, too, because it was about value, about materials, what has true value. I didn’t think Stanford would be stealing our gold, but apparently he’s trying to, or he is, or I don’t know. I don’t really know.

Let’s talk about the upcoming “Beam Drop” in Antwerp: you did it in 1985 and you’ve done it in Brazil in the meantime, too, right?

Yeah, the one that was done in 1985 was destroyed, I think, four years later. Not just my sculpture, but this whole place called “Art Park,” it was run by the city of Buffalo in Upstate New York, and they decided to destroy all the works. The other one is an 11-meter square, and maybe three or so meters deep. You dig out the dirt, then you put two thirds of the dirt back in, but the dirt now is loose; then you pour about a meter of concrete on top, and then you have 60-70 large steel beams, different shapes, different lengths, and you use a crane – also, you put a retarder in the concrete to slow the hardening process down –, you take the beams and you pull them up to about 120 feet, and then I have a special tool: you release the beams and it all comes down like pick-up sticks. They go through the concrete, and the finished product is a little bit like Pompeii. You can tell that some cataclysmic force happened and it became petrified. So, it’s different from standing beams upright and pouring concrete around: you can see the splashing, sometimes one beam would hit another beam, and you can see that it freezes a giant force – like the history of something, of a moment in time. It’s always a lot of fun; it’s really fun to watch them come down, and you can feel the earth shake. And I think that work is political, in a sense.

How so?

You know, the steel I-beam is the backbone of corporate architecture. And all those skyscrapers, the structure of those buildings, is built with I-beams, and they’re very, very serious. The corporations are serious and the architecture is serious in the sense that I-beams are not things that we play with. By using the I-beam in a fun way, in a sense I undermine corporate architecture.

Does that make it anti-architecture?

Well, it uses the tool, the basic building block of corporate architecture in a completely different way. In the opposite way. The beams are not meant to be dropped willy-nilly to make a giant abstract expressionist sculpture; it’s not their purpose in life, initially, you know what I’m saying? They’re very serious. They were made to make bridges or buildings, and, for example, the people who handle the beams, the steel workers, their job is never to drop those beams. Never. Now in this case they’re doing the exact opposite: they’re dropping them and letting them fall, as they will. Maybe I’m stretching it, but I feel I’ve done something slightly subversive.

You said earlier that your pieces work like a science experiment where you don’t know the outcome, though the “Beam Drop” pieces should be quite rehearsed by now, since you’ve done them more than once…

But they’re always different!

Certainly, though by now you kind of know the procedure and you do know that nothing bad is going to happen.

Well, that’s not true. You have to be very, very careful, because if one of the beams hits you, or hits a viewer or a crane operator, it’s probably not even a trip to the hospital, right? It’s a trip to the morgue. So that’s not true. There still is some danger involved. You know, I’m trying to minimise it; I mean, we have to get a contractor… it’s very serious business. Just because it’s been done before, doesn’t mean it’s not dangerous. And they’re always so different, it’s like if you splash paint on a canvas, you’re not going to get two canvases that are alike.

Right. Since this one is about a very tangible backbone of our society, I also wondered whether you’re interested in changes and developments on a way smaller level, meaning everything digital that’s happening right now. Are you interested in dealing with that and, for example, using techniques in the opposite way somehow?

No, I’m not. I think there’s a problem with the Internet and Twitter and all those things. I’m not personally interested in using them, but I can see the benefit of using computers to make an artwork. I’ve had the plan for a long time to make a three-dimensional map in real time, of large cities, like New York or Los Angeles. And then the three-dimensional object would be based on the time it takes to get from A to B; in peak traffic hours this three-dimensional blob would greatly expand in size. It would be about time, not distance – it doesn’t matter if it’s 10 miles or 10 kilometres, if it takes you three hours to get there, then it’s three hours away. And then it’s as far, for me, as going to Chicago or something. I could see using computers to make an artwork, but I am not interested in using the Internet itself. I think the problem is that people feel empowered by it: it used to be that you had one person who just was a crazy nut, whereas now because of the Internet they go, “Oh, I have several sympathisers.” So this absolutely open form, I think, gives strength to problematic points of view, and I don’t know what to do about it.

But doesn’t that make it even more interesting?

I think one of the things about technology is that you should always feel free to reject it. Just because you have three television sets in your house, doesn’t mean you have to have them all on at once. Just because your Mercedes can go 250 kilometres an hour, doesn’t mean you have to drive it that fast. I think part of living with modern technology is rejecting technology, too: not being a slave to it. You can see people are just enslaved: they are on their cell phones while they’re driving, even when their plane lands they have to talk, “Oh, my plane just landed.” This is non-information at some point and it becomes a distraction. You have to feel free to take some and maybe leave a lot aside. It’s the same with doctors: the more sophisticated the medical instruments get, the worse the diagnosis gets. I’ve heard stories that, now that people have GPS in their cars, they don’t use their common sense. If the GPS says, “Take a right, go up that road, go up that road,” – the road gets smaller and smaller, then there are rocks, then there’s snow –, but as long as the GPS says “Go,” I mean, look out your window! Your eyes should be telling you to turn around.

So, what are the forces that you are personally interested in right now, that you might work with in the near future?

Well, I’m working on a large sculpture now; this is the third year we’re working on it. It involves miniature cars, Hot Wheels cars, and we’re making a city. We have 1,200 of them circulating; a little bit like a roller coaster, they’re taken to the top and then they’re released. They run free through the whole city. They make a tremendous noise, so it’s a model of an active urban situation. I made a small one about four years ago that went to Japan; it’s called “Metropolis.”

When do you think the new one’s going to be finished?

I don’t know. I made an airplane factory at the Tate about ten years ago, and it was a spectacular failure, it never worked, so we’re trying to get that to work, too.

Do you usually have a plan when things should be finished, or are you just working away?

It depends on the situation. For example, this “Metropolis II,” the big one, people already wanted to purchase it. I had collectors who wanted to buy it before it was finished, and give me money. They really wanted to close the deal.

Which is a good thing, usually.

No, no, it’s not a good thing. I refused because it stops the freedom; I mean, often when I’m working for a client, and they have already paid, what if I want to make it different, or if I want to spend another year building on it? There’s a conflict, and it’s much better to say, “When it’s finished, we’ll let you know. We’ll tell you the price and you can decide yes or no.” But until then I don’t want people coming to my studio and inspecting and going, “Well, you said it would be finished by now!” That takes away all the pleasure, so for me it’s not a good thing. I want to make it as well as I can, to my level of satisfaction. I don’t want to have things yanked out and made to a pre-determined price; I think that’s crazy. It’s nice to have people who want to buy things before they’re finished, but it’s a little bit problematic. Also, to me it’s a great luxury to not have a date when I have to have it finished. There is no deadline. The deadline is when I feel it’s complete. But of course there are other things: “Beam Drop” will be done in one day.

words: rnk/trifeca.org (lodown #66)